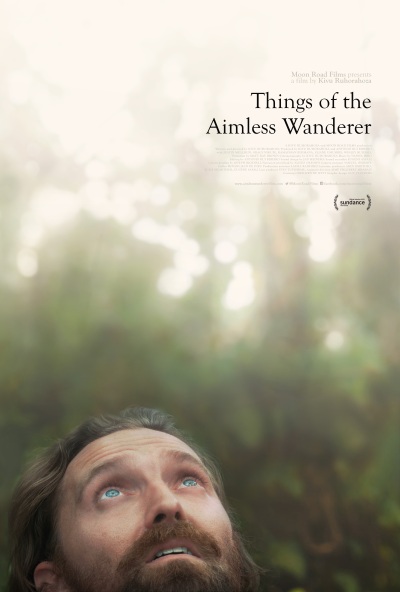

Moon Road Film’s first narrative feature “Things of the Aimless Wanderer” by Kivu Ruhorahoza has made it to Sundance 2015! We are over the moon of course and are now working hard to produce all the needed deliverables, before we set out to Park City, Utah in January. We are 99.9% there.

We are incredibly proud to be there and share the spotlight with an array of great films, actors and directors, as part of the New Frontier section of the festival (and beyond). As with Kivu Ruhorahoza debut feature “Grey Matter” (Matiére Grise), when I first set my eyes on the raw rushes I knew we had another great film in our hands.

Shot in its entirety using the inexpensive but powerful Black Magic Cinema camera and a set of Samyang prime lenses, this film was made without any funding other than the producers’ own resources and contacts, relying on Ruhorahoza’s eye, the strength of his story, a powerful soundtrack and the performances of its young cast as its the driving force.

The film playing in his head

by Antonio Rui Ribeiro

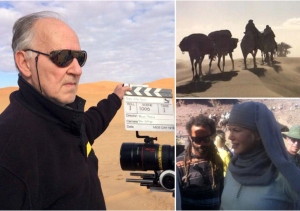

When I was in Rwanda in October 2013, shooting a film for Al Jazeera English called Justice Seekers broadcast on occasion of the 20th anniversary of the Rwandan genocide, I met Kivu in Kigali for a catch up and a few drinks. One thing was clear: this was a filmmaker with a sense of urgency, a need to go and shoot his next film no matter what. Little did I know at the time that when he said he wanted to shoot something and had these images in his head, of a man from a not too distant past roaming the forest, that these images would then become Things of the Aimless Wanderer.

Like Balthazar, a character in his first film Grey Matter, Kivu Ruhorahoza too started to imagine the story and playing it out in his mind with such urgency, that despite a lack of finance (and I mean film financing), things went ahead anyway. Driven by an obsession to tell a story.

After an intense shoot, temporarily halted due to a motorcycle accident involving the lead actress Grace Nikuze, a lack of hard drives and time constraints with some of the key locations, Kivu finally arrived in London in early September for the post-production to begin. In the first few days, I watched two films that influenced Ruhorahoza’s approach in the making of Things of the Aimless Wanderer: Chris Marker’s film Sans Soleil and Manuel Gomes’ Tabu (2012). After watching both films and studying Kivu’s concept and mock-up of the narrative, the ground was set for the post-production journey to begin.

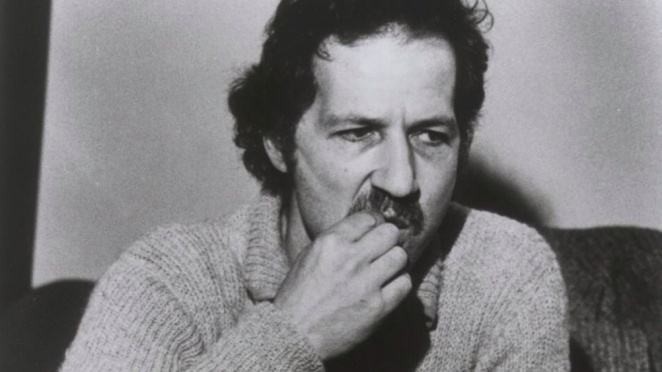

Photo by Laura Radford, http://www.lauraradford.com

About “Things of the Aimless Wanderer”

by Kivu Ruhorahoza

A white man meets a black girl. Then the girl disappears. The white man tries to understand what happened to her and eventually finish a travelogue.

When the first explorers visited East Africa, the local Bantu populations called them “wazungu”. The word comes from the verb “kuzunguka”, to spin around, as a result of the explorer’s propensity to get lost in their wanderings…

Things of the Aimless Wanderer is a film about the sensitive topic of relations between “Locals” and Westerners. A film about paranoia, mistrust and misunderstandings.

Half a century after African independences, one would have imagined that relationships between African “intellectuals” and the West would be appeased by now. But more than ever before, tensions are rampant and mistrust is at its peak. In these times of easy access to the Internet, those who consider themselves depository of African authenticity are alert to the Things of the Aimless Wanderer. The ways of the Westerner.

1. Fear of hybridisation: The fear of hybridisation engenders violence. Real or perceived. All societies are violent. And violence is normal. “Authentic identities” are sweet illusions and those who think it is their responsibility to preserve them are dreamers. Dangerous dreamers. There are more and more African voices rejecting everything “western”. There is increasing paranoia about how far we can go at embracing the ways of the westerners. African intellectuals have failed to conceptualise African modernity and the only possible modernity left for us is now Western. There is growing resentment towards Westerners defining the new cultural norms and being the sole narrators of the African story whatever that is. The “foreign correspondent” is a particularly hated figure in modern Africa because he seems to have a monopoly of the opinion on African matters.

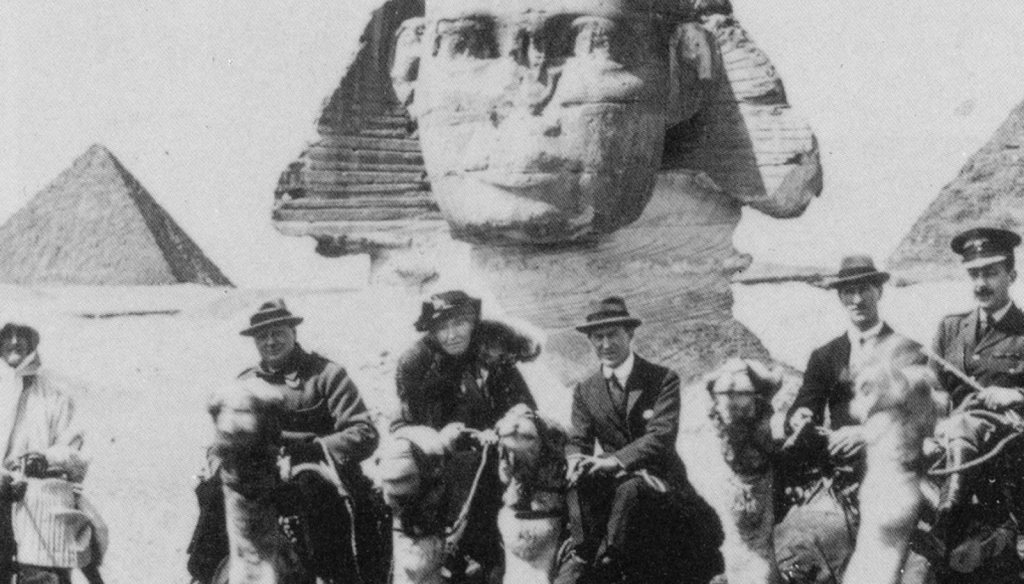

- White Man’s Burden: The foreign news correspondent believes he is invested with a sacred mission. He has romantic dreams about the status and lifestyle of a news reporter on the African continent. There is still a certain type of glory, early 20th century type of glory, that one can easily achieve in this part of the world. It is cheap glory but it is glory nonetheless.

3. Patriarchy: All the males in the story feel like they can save the young woman. In their own ways. The foreign news correspondent wants to save her from her reactionary males. In his opinion, she is the typical, mysterious “African princess” that these men can’t appreciate the right way. The local men want to save her from the immoral influences, the Western ways of the foreign correspondent, the Things of the Aimless Wanderer…

My thoughts on the film and the process of making it

1. I am not afraid of black magic. Cinema is magic. The moment I heard about the Blackmagic Cinema Camera and its specs, I realized that many of us would have no excuse anymore. I’m a little surprised many fellow filmmakers are still reluctant about all this new technology… Can they afford to? After a disappointing three years trying to traditionally develop my second feature film, Jomo, I decided I was done. I would try something different.

- I am tired of being nostalgic of things I never knew. I’ve never worked with millions, I’ve never worked with 35mm, not even an ARRI Alexa. Why impose myself those prerequisites to make a feature? Following the same logic, I don’t always need to conceive films using models invented in the 20s and 30s. Is it possible to write a script in MS Excel? Certainly. Do I really need Courier or Courier New fonts to write?

- I don’t want to become a professional brainstormer. From 2011 to 2014, I talked about ideas, wrote treatments, pitched them, brainstormed, over and over again and got pretty much nothing done.

- If it takes me eight years to make a film, it better be a masterpiece. Not another unoriginal, technically perfect but emotionally laborious movie. Filmmaking is no longer for the “chosen ones”. Films are magnificent and complex objects but the process of making them needs to be demystified and lightened up.

- “A lot of people are unnecessarily slow. It drives me crazy. One of my M.O.’s is “Just get it done.” I hate all that pitching and stuff behind the scenes: “Oh, we have to get this to make it.” However I can bypass all that and just make the movie, I do. I’m proud of that. I can actually get these things done. That’s the worst! Waiting around and talking about movies, waiting for this or that deal? If you truly love filmmaking and getting things done, just go and you can do it.” James Franco

- It’s honourable to want your crew and cast to be paid normal wages but it’s even better to make a film and finish it and get it seen. By any means.

- There is a new and unpleasant trend of “writing workshops”. This is where original ideas go to die. I don’t want 86 hands on my project. What I needed for this project was a compact group of talented and committed people who could preferably accomplish more than one specific task. I wanted trust, instinct and intuition to have a preponderant place in my creative decisions. With no budget, no shooting permits, a lot had to be improvised during production.

- Sony Labou Tansi, the great Congolese author, once said he makes bastards to the French language. He felt that reproducing the exact same, or even better, French syntax was a violent denial of who he was. I intend to make a few bastards to “cinema”, that kind of cinema where the most banal and ordinary films are developed for over five years, last 90 minutes and cost three million dollars for a one-week theatrical run and a 0.5% return on investment, if you are lucky.

- Am I afraid of winning the “Most Pretentious Film Award”? Yes, a little. But, damn, it feels good to work on my terms, improvise, dare.

- I want to work. I just want to work.

In fact, wherever we went in the evenings, they all seemed to be very large houses. But I couldn’t help feeling an emptiness, a certain abandonment about them. Some of the houses, still bared the scars of the genocide, with bullet holes in the wooden beams and slightly twisted window frames, not quite shutting properly. In one particular house, where a Swedish journalist was living, there were a number of people killed there. And despite the sense of occasion our visits seemed to have (maybe because I was new there, it just felt that way), this uncomfortable truth seemed to always be there in the background, staring at you.

In fact, wherever we went in the evenings, they all seemed to be very large houses. But I couldn’t help feeling an emptiness, a certain abandonment about them. Some of the houses, still bared the scars of the genocide, with bullet holes in the wooden beams and slightly twisted window frames, not quite shutting properly. In one particular house, where a Swedish journalist was living, there were a number of people killed there. And despite the sense of occasion our visits seemed to have (maybe because I was new there, it just felt that way), this uncomfortable truth seemed to always be there in the background, staring at you.